“The priest Xiangyan (Kyogen) said, ‘It is as though you were up in a tree, hanging from a branch with your teeth. Your hands and feet can’t touch any branch. Someone appears beneath the tree and asks, ‘What is the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West?’ If you do not answer, you evade your responsibility. If you do answer, you lose your life. What do you do?’”

Gateless Gate, Case 5

James Ishmael Ford

For me, my spiritual life must be engaged in a conversation with modernity and its challenges. And of these the principal engagement must be with the challenges found within the natural world and our human consciousness as an artifact of that natural world.

The what you see is what you get as the spiritual path.

And with that the wisdom of what some Buddhist spiritual directors call “no escape.”

I find it important to engage as honestly and heartfully the challenges of our contemporary scientific world view and with that specifically the theory of the self-organization of matter and energy.

This can be a question about God as a conscious entity in some sense similar to human beings. And it is. But what I find most challenging is the centering of humanity. I have noticed the way people sometimes describe God is in fact little more than a big version of us. As I contemplate all this, as I live in the world I see and feel and smell and taste and touch and which my brain organizing into stories, I have trouble feeling compelled to believe anything about a specialness to me, or to a bigger me.

This view is supported to my mind by a variation on the argument from design. How can anything so vast, and specifically, where the solar system has such a negligible and peripheral place (i.e. at the outer edge of a galaxy and where human existence relies on such an obviously tenuous combination of conditions), give any kind of centrality to human existence?

For me the ultimate challenge is to any idea of a conscious organizing principle. That is the self-organizing of the universe seems to be to challenge any necessity to believe in a creator God, that deity that looks like me. If there is any such thing, its relationship to our planet and its occupants seems so vastly removed as to have no involvement in our individual or collective lives. The entire arc of human existence seems to have no need of an external involvement.

So, no God in the sense we usually use the term. And with that no specialness in regard to, well, me. Or you.

In the light of Buddhist observations generally supported by scientific investigation, suggests there are no abiding elements to an individual human being’s consciousness. We arise naturally out of a complexity of causes and conditions. That consciousness is what it is in a dynamic evolution from birth to death. Death here being a shift in those causes and conditions. At which point it, such a nice way to say you or I, ceases to exist.

At least in the sense of the passage of time as is experienced in human consciousness. There are other ways of understanding time and with that our temporality.

We are, after all, in some last analysis all of us entangled. Intimate beyond the capacity of words to describe.

And, of course, there are other uses of the word God. I find the sum total of everything, for instance.

It all is deeply weird. And wonderful. And sometimes terrifying.

And with that the ancestors offer up a koan.

“The priest Xiangyan (Kyogen) said, ‘It is as though you were up in a tree, hanging from a branch with your teeth. Your hands and feet can’t touch any branch. Someone appears beneath the tree and asks, ‘What is the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West?’ If you do not answer, you evade your responsibility. If you do answer, you lose your life. What do you do?’”

The trope “What is the meaning of Bodhdharma’s coming from the West?” turns on the legends of the founder of the Zen tradition in China. But it is a shorthand for, why? Why this? It’s also a shorthand for the saving vision. What is awakening?

Our way speaks of not one and not two. What does that mean?

In at least one or two strands of that family of traditions we clump together and call Hinduism it is said the world is maya. I understand that word usually translated as illusion. But recently I learned from the scholar priest Francis Tiso that maya can be translated as “magical display.”

In our tradition the world can be described as illusion. Dream is probably better. And magical display is better, yet. The phenominal world, the world where we occupy that very tiny corner is, as noted, deeply weird. One thing seems pretty obvious, in several senses that are compelling, everything is connected in a wildly shifting and changing, but always connected way.

Magical display.

And, there’s something to be found in that always connected thing. It might be called one. Zen likes sunyatta, which we often translate as empty. Empty of abiding substance. As they say thoughts without a thinker.

And Zen’s saving grace is how we can come to encounter these two things as not two exactly, and not one precisely. Among some of my wiser friends, I’m told this place, if we can call it a place, is where the word God starts to make sense.

Certainly spiritual language begins to feel appropriate. As I’ve come to name those fundamental shifts in our relationship with reality in Zen’s awakening moving in their mysterious ways as “magical realism,” I was immediately caught up the term magical display. I’ve also seen another literary term, “sacred realism.”

I look at my life and the lives around me. It’s real. And it’s magical Illusion. Sure. From one angle. The whole thing from another.

Sacred realism. Magical realism.

This stuff, this life. Intimate and inviting.

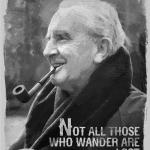

No escape.

Intimate.