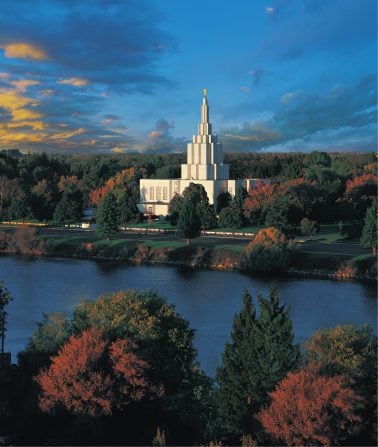

(LDS Media Library)

***

Back in 2005, I was invited to write a little mini-essay for the Church’s official website. Here it is:

“Everyone Else Makes Such Lonely Heavens”

I thought of it because of a complaint against the Church that I saw recently, and that I’ve come across several times over the past few years.

I find it exceedingly odd.

Roughly, it goes like this: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is to be condemned because it cruelly threatens people that their marriages and families will be broken up at death if they don’t join the Church, fork over at least ten percent of their incomes for the enriching of the Brethren, and get themselves sealed in a temple owned and operated by LD$ Inc.

The complaint seems to presume that every other church teaches and has always taught that families will be together forever without temple sealings, and that it’s a heartless Latter-day Saint innovation to come along and say that that’s not true.

But traditional Christianity has long taught that marriage and family relationships will be terminated at the grave.

Read Dante’s “Divina Commedia,” for example, to get a glimpse of historic Christian orthodoxy on this matter: To the best of my recollection — and I’ve read it several times, though not, now, for at least several years — there isn’t a single intact married couple or family group anywhere in that great, long compendium of medieval Catholic doctrine and commentary. Not in the Inferno. Not in the Purgatorio. And not even in the Paradiso. Nowhere. Everybody in it, whether damned or saved or in between, is a lone individual, a social atom (as it were).

Here’s a sampling of the relevant phrases from mainstream Christian wedding services:

“as long as you both shall live” (Episcopal, Methodist)

“so long as you both shall live” (Unitarian)

“until we are parted by death” (Episcopal, Methodist)

“as long as we both shall live” (Presbyterian)

“so long as we both shall live” (Quaker)

“until death parts us” (Lutheran)

“as long as we live” (Lutheran)

“until death do us part” (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox)

“till death us do part” (Anglican [Book of Common Prayer])

“all the days of my life” (Catholic)

Nor can I think of any other major religious faith or tradition that teaches anything other than the effective rupture of marital and family ties at death. (There’s a nice passage at the very end of the tragic tale of Leyli o Majnun, as told by the twelfth-century Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, that seems to hold out a satisfying hope in one particular case. But that romantic poem is scarcely representative of mainstream Muslim theology or doctrine.

And, needless to say, atheism doesn’t exactly promise an eternal companionship for spouses and families, either.

This weird objection — that, somehow, we Latter-day Saints have come along and threatened people with divorce in the next life unless they surrender to us and fork gobs of cash over to us — strikes me as rather like a situation in which someone is drowning in a swiftly moving river. A huge waterfall looms. A benevolent onlooker grabs a life preserver and throws it out to the drowning person, who shows no interest in it whatever. The hopeful rescuer reels it in and tosses it out again. However, the drowning person, rapidly moving toward the roaring cataract, ignores it a second time. Increasingly worried, the would-be benefactor runs along the river bank, pulls the life preserver in a third time, and throws it out once more to the drowning person. “Grab it!” he admonishes. “If you don’t take hold of it, you’re certainly going to die!” “How immoral of you!” responds the soon-to-be-dead person in the river. “Now you’re threatening me with death unless I accept your precious little flotation device!”

***

Some time back, I read a book by Brian Clegg entitled Are Numbers Real? The Uncanny Relationship of Mathematics and the Physical World (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2016). It deals with a really interesting topic that, in my view, may suggest the falsehood of materialist/reductionist views of the universe.

I’ll share just a few passages from it:

“Would numbers exist without people to think about them, or are they just valuable human inventions, the imaginary inhabitants of a useful fantasy world?” (1-2)

“Similarly, when mathematicians played around with an idea like the square root of a negative number, called an imaginary number, they were initially simply enjoying a new direction to take their mathematical game. But, as it happened, because of the rules they decided to apply to this magical class of numbers, it became a hugely useful tool for physics and engineering.

“No scientist or engineer ever said prior to the introduction of imaginary numbers, ‘What we want is the square root of a negative number. They would really help us with this problem we’ve got.’ Similarly, no one in mathematics thought, ‘How can we solve this particular problem that the physicists have?’ before dreaming up imaginary numbers. The mathematicians just played with the implications of their new concept and the set of rules attached to it. The applications emerged later.” (7-8)

“Some scientists, such as physicist Max Tegmark, go so far as to suggest that the universe is mathematical. That numbers aren’t just real, but are what make everything happen.” (10)

The Pythagoreans, whose motto, carved on the lintel of the door to their principal school, was “All is number”: “They were of the opinion that everything in the universe was structured on numbers — that numbers were not merely a human creation, but provided the underlying architecture of reality.” (30)

“You could . . . say that mathematics is an agreed fiction, a shared mental world that mathematicians agree to collectively inhabit. But their world isn’t allowed the looseness of literary fiction, because here all the rules have to be pinned down and agreed. As long as a piece of mathematics is consistent with those rules it is acceptable, whether or not it has any parallel with the physical universe. Yet we keep coming back to the fact that a sizable subset of mathematics not only has parallels, but has an uncanny ability to mirror what the real world can offer. It could just be because so much of the essential structure that mathematics is built on — like the nature of whole number arithmetic — started as a reflection of the real world.” (52)

Brian Clegg is looking at the same general issue as that raised by the Nobel-laureate physicist Eugene Wigner in his famous 1960 paper “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences.”

The English physicist, astronomer, and mathematician Sir James Jeans (d. 1949) had perhaps been thinking along similar lines when he remarked, in his 1944 book The Mysterious Universe, that “The stream of knowledge is heading towards a non-mechanical reality; the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter. . . . we ought rather hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter.”

***

My wife and I had dinner last night — Indian food — with Royal Skousen and his wife and daughter. He is one of the greatest and most committed scholars in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and his wife’s contributions to his work have themselves been significant. Dinner was followed by fascinating conversation about books and art. I’m blessed to have such friends, and such experiences.