by Janine Giordano Drake

If you peruse the new books section of Christian book catalogs these days, you’ll find yourself beset with jeremiads about false messiahs and the imminent collapse of the American church. First, there’s Ryan Burge and his team of pastors and political scientists who have been arguing that “We are experiencing the largest and fastest religious shift in US History.” They use research going back about fifty years to claim that the number of Americans who do not participate in congregational life is higher than it has ever been. Then, you’ll learn that part of the culprit for this demographic shift is “Woke Jesus,” a “false messiah destroying Christianity.” If you keep reading, you‘ll encounter a set of books which may be best explained as “Urgent Appeals.” You’ll find an explanation for “Why Social Justice is Not Biblical Justice.” You’ll find the appropriate “Christian Response to the Cult of Progressive Ideology.” You’ll find out “How the Social Justice Movement is Hijacking the Gospel.” These books argue that race and gender and culture are unnecessarily divisive, worldly categories and we should be suspicious of any efforts which purport to remedy historical injustices. They suggest that we need to practice the posture of forgiveness and reconciliation and moving on. And yet, if you get to the end of these books and conclude that cultural identity categories are worldly idols, you’ll then become further confused at the American flag decor for sale in the “home” section.

Over the next several months, I’m going to read through these books and analyze them as a historian of socialism, Christian Socialism, and liberal Christianity. Who are “Woke Christians” and how do they differ from the socialist, liberal, and Social Gospel Christians of the past? What is “neo-Marxist critical theory” and when did it start impacting Christian dispositions toward Biblical hermeneutics, theology, ecclesiology and history? To what extent is this debate between today’s evangelicals and “woke Christians” different from the debates over socialism or the “Social Gospel” during the last century? To what extent have we re-opened old and unresolved debates over how to define the Kingdom of God? I should briefly introduce myself. I am a person enriched by the evangelical tradition, the Roman Catholic tradition, and the Lutheran tradition. I have also been enriched by the Marxist and anti-racist traditions of activism and critical theory. I have many loved-ones who worry about “woke Christians,” people like me, undermining the Christian witness. If you are one of those people, I take your claims seriously and want to earn your trust as a historian and fellow traveler on a journey to better understand the dissonance in today’s Church.

Mass Religious Dis-Affiliation in the Gilded Age

I thought we would start this blog series with what I see as the most fundamental question of all: Is it true that we are experiencing an unprecedented exodus of Christians from church life? Burge and others are right that social surveys reveal a precipitous drop in religious affiliation over the last twenty years, accelerating over the last decade. However, if we go back more than a century, we find that church affiliation rates have seen this much flux before.

Join me on a journey into the late nineteenth century, about a generation after Western lands became available for white settlement on the public domain. This was a moment when wealthy white families in cities were getting their children an excellent education and sending their sons out into the well-paid professions of medicine, law and business. They were sending their daughters to work in “social work,” a broad category including nursing, settlement houses, residential rehabilitative institutions, and other forms of “charity work.” Blue collar whites, including men and women, worked in the skilled trades, including machine work, metalwork, clothing production and the production of luxury goods like cigars, beer, hats, and coats. Cities also had a large migratory population that included men who rode the railroads in search of temporary work. Some of these poor Americans took their chances out West in jobs on ranches, in mines, or in the extensive meat packing plants around Chicago. Mark Twain called this moment the “Gilded Age” because of how much it glittered on the outside—the large American mansions with a full team of servants! The beautiful clothing and luxurious lifestyles for the rich and famous!—while such a large fraction of Americans lived in poverty.

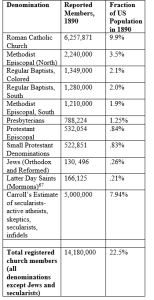

In this last Gilded Age, less than 22% of Americans had any religious affiliation at all.

The tradition that claimed the fidelity of the largest number of Americans was Roman Catholicism. Parish priest reported more than 6 million Americans as members of their congregations. However, because the Roman Catholic church in the United States was still an “immigrant church”–a conglomerate of missionary churches which answered to European national churches, it did not behave in the United States like a single organization. Meanwhile, the next most popular religious tradition was that of Methodists, a tradition popular among the Anglo aspirant-classes in the cities and throughout the countryside, but which still only claimed about two million Americans as members (scarcely more than 3.5% of the US population). Sure, there were beautiful churches that reached to the sky, as well as prominent missions that offered indispensable education and social services to the poor. But, 78% of Americans in 1890–the vast majority of Americans–didn’t regularly show up at any official house of religious worship.

What were all those unchurched Americans doing? Were a large number among this group atheists or agonistics, believers in the “modern” evolutionary theories and historical criticism of Biblical texts that appeared to discredit Christian teachings? Or, were they a Gilded Age version of exvangelicals, people raised in the faith but pained by religious leaders for the hypocrisy and corruption of their leaders and institutions? Were they young people who met in homes and bars to discuss books by Leo Tolstoy, Oscar Wilde, Edward Bellamy, and Charles Sheldon–restless “reformers” eager to imagine a new kind of church that was much more “relevant” and connected with the needs of ordinary people? Or, were they middle-aged Christians annoyed with the politics of their local clerics and disenchanted with the minutiae of inter-Protestant rivalries? The Gilded Age Americans who voted against conventional churches with their feet were every one of these categories and more.

Henry Carroll, the Methodist minister and theologian who ran the US Census of Religious Bodies in 1890 and 1906, estimated five million Americans—a figure larger than all American Protestants combined–were woke. No, of course he didn’t use the term “woke.” He called these people who cancelled church and held out for a different kind of world “secularists, active atheists, skeptics, secularists and infidels.” He was right when he wondered if evolutionary theory and socialism, independent ideas but also working in synergy, were serving as the gateway to church cancel culture. He was also right that many among these protesters to church thought of themselves as Christians, even as they were “unbelievers in the Church.” Even if Carroll resisted the urge to put all these folks in a single box, he was obsessed with this phenomenon of church dis-affiliation and the role of politics (particularly, socialist politics) in producing this shift. Carroll deserves much of the credit for the fact that evangelical discourse to this day is still informed by rigorous demographic and cultural analysis.

In my book, The Gospel of Church, I followed the story of “woke” Christians in the Gilded Age and where they ended up after a twenty-year dialogue with church leaders. Let me assure you that “Woke Christians” are nothing new to the story of American Christianity. Rather, they have a story and I would love you to join me in unpacking it.